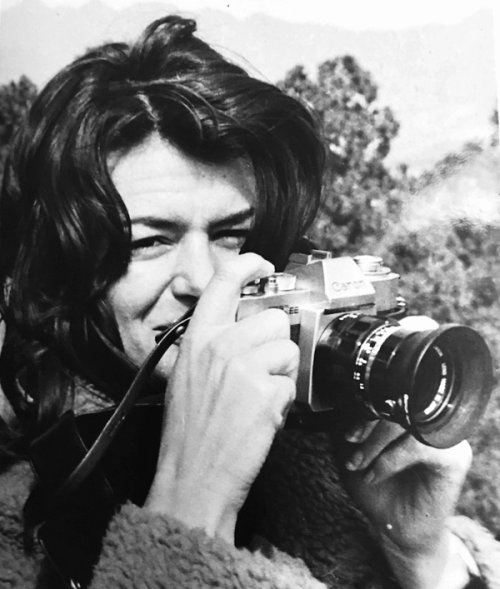

Maggie Keswick Jencks

A View From the Frontline

1994

Maggie Keswick Jencks, Charles Jencks’ second wife, wrote this text while battling breast cancer, which returned after a period of remission. It follows Maggie’s personal experience of fighting the disease, while offering criticisms of how public health systems approach and treat cancer and cancer patients. First published in a medical journal, this piece was later republished as a booklet that formed part of the blueprint for Maggie’s Centres – a charity that has built many cancer caring centres designed by renowned architects. Charles Jencks continued work on this project after Maggie’s death, and the first centre opened its doors in 1995. Since then, more than twenty centres have been built both in the UK and internationally.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of cancer hits you like a punch in the stomach. Other diseases may be just as life-threatening, but most patients know nothing about them. Everyone, however, knows that cancer means pain, horrible treatments and – though no longer quite the unmentionable Big C of twenty-five years ago – early death.

Cancer does kill, of course, but fear – compounded by ignorance and false knowledge – is a paralysing attack in its own right. The myth of cancer kills as surely as the tumours.

I am a sanguine character and for forty-eight years my life was exceptionally easy –so easy that for me breast cancer seemed almost like a payment of dues. After lumpectomy, a further incision to the margins and finally mastectomy, I decided against having an implant because it seemed false to pretend it hadn’t happened. I also didn't like the idea of a silicone sac sewn into my body for appearance's sake: since it couldn't have any feeling in it, what was the real point? And perhaps I was also relieved (and here I am conscious of how lucky I am in my marriage) to find that I could survive amputation and not feel diminished: my Amazon chest is a battle scar, an affirmation.

I was amazed and touched by how much my friends and family minded about my having cancer. Recovering from surgery and radiation I was cushioned in love and thoughtfulness, and the moments I had of panic, though violent, were brief: thousands of women have primary breast cancer, are treated, and that’s it. My cancer, on the inside of the breast, was an aggressive type, but none of the lymph nodes under my arm showed any malignancy. I had six weeks of radiotherapy, then took Tamoxifen for two years. There were no side-effects.

Metastases

It took five years to return. I had put cancer so far behind me that I didn’t recognise it. The pain in my back, which sometimes, when I was alone, reduced me to sobs, felt much like an old herniated disc playing on my sciatic nerve. The increasing exhaustion was presumably due to pain, with maybe a bit of anaemia? Or menopause? My doctor did a few blood tests; they showed nothing special. I asked for a CT scan; there was a question over whether some speckles up and down the spine needed watching. I was told to return in six months. I accepted that. Such is denial, such is ignorance.

It helped us later to be told by an American oncologist that an earlier diagnosis of the metastases would have made little difference; ‘If only…' is a lousy thought to deal with.

Eventually, in Scotland with my mother, I felt so ill that we took my temperature. It was 39.7. The cancer had spread to my liver, bone and bone marrow. A compassionate local consultant who saw me told my husband not to haul me round the world looking for treatments, since we could gain no more than a brief extension of life with increasing loss of quality. How long have we got? ‘The average is three to four months (and I'm so sorry, dear, but could we move you to the corridor? We have so many patients waiting...)’.

Treatment

However, through our local hospital’s weekly cancer clinic we also heard about a trial in advanced metastatic breast cancer run by Dr Bob Leonard at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh. I fitted the criteria for treatment with high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell replacement. Dr Bill Peters at Duke University, North Carolina, had already treated several hundred patients with a similar regime and the average length of remission for his patients after treatment was then eighteen months. It seemed like a lifetime.

The preliminary three-month course specified weekly Adriamycin and continuous 5FU via a Hickman line. My cancer proved chemo-sensitive. But, strangely, I found that the process of deterioration which my body had now begun had also affected how I thought about death: in running down, my body had in some way prepared my mind to accept the ending of my life. Eventually, the most difficult thing was deciding to give up the certainty of death for the uncertain prospect of a stay of execution: if I got into fighting mode, and it failed, would I ever get back again to this precariously balanced acceptance?

Conventional and unconventional alternatives

My husband read and rang everything and everybody who knew about breast cancer, in America, in Britain, in France and in Germany. I found this quite exhausting but also understood that it was necessary to him as his way of dealing with my illness. Friends rang us with news of remissions achieved by the administration of shark cartilage, carnivorous plant extracts, the laying-on of hands, hydrotherapy, diet, regimes of pills, oxidisation. In his extremely well-balanced book Choices In Healing, Michael Lerner likens cancer to a parachute jump, without a map, behind enemy lines. There you are, the future patient, quietly progressing with other passengers towards a distant destination when, astonishingly (Why me?) a large hole opens in the floor next to you. People in white coats appear, help you into a parachute and – no time to think – out you go. Aaaiiiieeeee!

If you're lucky the parachute opens. You descend. You hit the ground. You crawl upright. You are surrounded by a thick fog through which a crowd of dimly discernible figures call and gesture ‘Here! This way!’. But where is the enemy? What is the enemy? What is it up to? Is it here, behind this bush? Over there? Near? Far? And which way is home? No road. No compass. No map. No training. Is there something you should know and don't?

The white coats are far, far away, strapping others into their parachutes. Occasionally they wave but, even if you ask them, they don’t know the answers. They are up there in the Jumbo, involved with parachutes, not map-making.

It is true that recently some of the parachute-makers have been asking new questions which may revolutionise the process: monoclonal antibodies; oncogenes; vaccines; DNA...all this research may lead us some day to a cure or cures, or at least delays and surer remissions. But can you promise me the magic parachute in a year? In two? In five?

Meantime I am down here in the war zone, trying to figure out my map. Responsible doctors are rightly fearful of charlatans preying on vulnerable patients, but intelligent patients start reading and soon realise chat the crack record in orthodox treatments in most cancers is itself not altogether reassuring, and the scientific method not as disinterested as it likes to suppose: it is legitimate to feel that a sum of various supports to the recommended therapy may boost one's chances. But how is the patient – utterly unequipped to deal with this barrage of suggestions and faced with doctors who are, at worst, downright anti any additional therapies and, at best, supportive but sceptical – to proceed?

Guerrilla warfare

In Bully for Brontosaurus the American scientist Stephen Jay Gould described the rare cancer, abdominal mesothelioma, he developed in his thirties. The scientific literature at the time described it as incurable, with a median mortality of eight months after diagnosis. Reading this soon after surgery he sat, stunned, for fifteen minutes. Then, into his mind came a great and stately procession of Bahamian land-snails – on whose small-scale evolution, treated quantitatively, he had been working for some years. ‘I am convinced,’ he wrote, ‘that this played a major role in saving my life,’ for the knowledge of statistics he had acquired from the snails allowed him to realise that median does not have to mean me: ‘Knowledge’, he wrote, ‘is indeed power, as Francis Bacon proclaimed.’

Counting up the reasons why he was unlikely to be at the high point of the statistical curve he stopped panicking: his chances, as a young, well-educated scientist with a strong will to live, were much better than the median. Mentally he began to push himself down the bell-curve and along into the tail. With a new warmth towards snails, we too set out to educate ourselves in cancer, and to see if there were complementary therapies – I thought of them as guerrilla tactics supporting the parachute jump – that might do the same for me.

Dealing with stress

The diagnosis had been as hard on my family as it was for me. For oneself it is possible to accept anything; not so for those one loves. Seeing the suffering of my husband, mother and teenage children affected me physically. At one time I could not sit, lie, or stand, listen or speak coherently because my shattered mind vibrated so violently through my body that I felt I might disintegrate. Later, yoga helped me re-establish some equanimity. Counselling helped me think more calmly about my children’s future.

Nutrition

The area, however, that sprang first to my mind as we looked for ways to encourage remission, was diet. If you ask your oncologist ‘What should I eat?’, 99 per cent will answer ‘Whatever you like! Eat well, keep up your weight!’ because they know the awful effect of cachexia. In America the Gerson experience scuppered nutritional therapies for cancer for more than twenty years; diet became ‘alternative’ and ‘unproven’ rather than ‘complementary’. In Britain some medical professionals grew wary as a few stories circulated of anorexically thin patients obsessed with avoiding many categories of food, under the influence, so it was said, of the Penny Brohn Cancer Centre's original – but now carefully reassessed – diet programme.

In our own experience, the husband of a cousin had died of a perfectly curable cancer while trusting exclusively to a macrobiotic diet – in the end, it seemed, dying sooner of malnutrition than he would have of the cancer he so feared. A woman friend died quickly of cancer because, too frightened of the treatments suggested by her doctors, she turned exclusively to diet as a cure.

My current remission is due to extremely powerful chemotherapy; without it I would certainly not be writing this now – so I am not for nutritional therapies on their own. But equally it makes no sense to me to be told that, while a diet restricted in fat, salt, and sugar and strong on fruits, fibre and vegetables is widely accepted as cancer preventative, once you actually have cancer you should be eating anything, everything, you fancy – fat, sugar, barbecues – anything!

In the months before my metastatic diagnosis I developed crazy cravings for sugar, chocolate (which I had never much liked before), and cakes and biscuits of all kinds. My skin also got drier and drier, till getting into a bath was impossible because I prickled all over as if rolling in a nest of hedgehogs. No creams or potions made the slightest difference. Since giving up all sugar, anything to do with hoofed animals, salt and the known carcinogens like smoked-cured foods, I have settled into a comfortable weight of around nine stone (somewhat higher than my weight at 40),all these nasty symptoms have disappeared and I feel terrific. I am perfectly aware that the scientifically trained physician may respond: ‘But that has nothing to do with it! You feel terrific simply because your chemotherapy worked, and you're in remission!’ But I believe I feel better than I have for years – from long before the cancer could have affected me – and that nutrition has been a major factor in this.

However, had someone told me to follow such a diet, I would have been appalled. (Life with such miserable meals! You must be joking!) I am not a natural vegetarian. I adore meat – roast lamb for Sunday lunch is my idea of caviar with trumpets; roast beef with Yorkshire pudding makes my heart sing. I love dripping, brains, and kidneys, liver and bacon, pork crackling, sausages, croissants, unpasteurised Brie, mayonnaise, French sauces, double cream, sponge cakes and black ginger cake lathered with butter. I don’t miss any of them.

Carolyn Katzin MS, a Los Angeles-based adviser on nutrition to the American Cancer Society, advises cancer patients ‘ideally, to restrict the intake of all fats to three tablespoons a day (including salad dressings, oil for stir-frying and other below-conscious-level fats) and eat the recommended minimum of five servings of fruit and vegetables daily. ‘ But,’ she stresses, ‘don't get frantic about food. Follow these guidelines eighty per cent of the time – and twenty per cent indulge a little.’ That was a lifeline. At home we eat a cancer-discouraging diet and – tens of vegetarian cookbooks later – our food is delicious. But we continue to go out to restaurants, to travel abroad and to eat with friends without panicking. If you know you can indulge it's remarkably easy to do so only moderately.

A lot more work needs to be – and is now beginning to be – done on the effects of nutrition on cancer, but, as Michael Lerner points out, there is, in fact, more in the existing scientific literature – albeit somewhat obscured and un-coordinated – than most doctors realise. Until we know more, no responsible doctor should brush off a patient's inquiry about food with an unqualified ‘There is no evidence linking nutritional therapies to cancer cures,’ without explaining that what he means is that there is an absence of scientific study, not a negative assessment based on fact.

Perhaps even more important than the actual effect of dietary restriction is that this is an area where patients can most easily take control of something tangible they can do for themselves. Even supposing nutrition makes no difference to mortality or quality of life, helping an interested patient to take charge of such an important aspect of their lives has powerful psychological implications.

Supplements

To my diet I added some homeopathic drops and megadoses (way over RDA levels) of vitamins A, C and E, selenium, chromium, potassium, and digestive enzymes to maximise absorption of nutrients. For a month I also took weekly injections to boost the thymus (thought by several alternative cancer physicians to be affected by cancer) until it was over-boosted and I developed a violently itchy reaction. I have no idea whether they helped me or not.

Supplements are controversial, even among complementary practitioners. Some think it simply a waste of money, others that real harm could result. Michael Lerner warns that research on rats fed with vitamin B12 showed powerful liver tumour enhancement and zinc has been shown both to retard and enhance – probably by its known antagonism to selenium – tumour growth.

Blood tests or hair analyses for deficiencies is expensive and takes time, but in cancer patients they commonly show an inversion in potassium/sodium levels and lowered zinc and selenium. Notable vitamin A, C and E deficiencies are common in patients undergoing surgery, radio- and chemotherapy. Could these deficiencies not account in part for patients feeling so ill during and after treatment?

More precisely, a study in the New England Journal Of Medicine (312: 1060 [1985]) showed that 69 per cent of chemotherapy patients who took supplements of 1600 IU dl alpha tocopherol (vitamin E) for a week before, and then all through, their treatment with Adriamycin, avoided losing their hair. That seems to me worth trying.

I had not read this at the time, and my hair did fall out. Since I was expecting it, however, I was rather interested to see how it would feel to be a Buddhist nun, and friends gave me a couple of hats in which I felt very cheerful. I got tired, suffered briefly agonising mouth ulcers, and twice missed a week of treatment for low blood counts – but, apart from desperate bouts of worry about my family, I felt remarkably well all through, kept up my weight, and slept easily.

Non-Western approaches

Since I grew up in Hong Kong it was natural, when we began the map-making, to think of Chinese medicine. Although it works on principles that are so different from those of Western scientific medicine that there is no real dialogue possible between them, most of my Chinese friends find both helpful. I expect the same is true of Indian Ayurvedic therapies. In my case we consulted Dr Li Ting-ming who runs the Institute of Chinese Medicine in London. Trained in Edinburgh in Western medicine, in Beijing in Chinese herbal medicine, and a cancer survivor herself, she believes powerfully in the part played by the mind in overcoming cancer. She gave me good, stern advice on the importance of the cancer patient's mental attitude, and PSP capsules from a mushroom used therapeutically in China for at least 2000 years. Recently subjected to trials in Hong Kong and China, PSP has proven value in minimising the side-effects of chemotherapy and radiation, and in preventing weight loss. The problem is that, as the mushroom exists only in remote mountains in the wild, the capsules are prohibitively expensive.

I also began a twenty-minute practice of Qigong exercises (which I still do) every morning before breakfast, and weekly sessions of reflexology. At first my feet were as if dead – I could feel almost nothing. Gradually, as I had more treatments, they began to reawaken. The sessions were both relaxing at the time, and energy boosting afterwards. Reflexology and aromatherapy are probably the most widely practised support therapies for cancer patients in Britain. We found that many nurses had taken courses in them to add to what they could freely offer their patients. In America, reflexology is almost unknown, but acupressure and acupuncture for pain relief are widely praised and practised.

Hospitalisation

When in hospital for the stem-cell replacement therapy I did unusually well until hit by an internal infection (it turned out to be pneumonia), which knocked me out for some weeks. I lost – partly because of the revolting hospital food – about 15 kg (33 lbs, two and a half stone). A month later I had a painful second bout of pneumonia. When eventually I flew to Los Angeles where my husband was providentially teaching –I was weak enough to need a wheelchair. I added still higher doses of vitamins. Within three weeks on my diet, Megace, these supplements, and in the California sunshine, I was bicycling up the beach.

Boosting the immune system

About this time we also heard about an immune-boosting ‘soup’. Developed by a Chinese biochemist at Yale, Dr Alexander Sun, for his mother, who had been sent home to die with Stage IV large cell adenocarcinoma of the lung. The soup appeared to have arrested her disease: six years after her ‘final’ diagnosis she is alive and tumour-free in New York. Other patients, and a small trial with thirteen participants in Czechoslovakia, have shown good results in a variety of different cancers, some with metastases in the adrenal gland, bone or brain. It seemed worth a try. I began taking a tub of Sun Farm Vegetable Soup every morning for breakfast. By the time we got back to Britain three months later, I had so much energy I needed tethering to the bed.

Just before discovering the soup, we decided to take an AMAS – Antimalignin Antibody in Serum – test developed by Oncolab in Boston, to monitor any malignancy still active after my treatment. In sera sent across the country the false negatives are 7 per cent and the false positives 5 per cent: one out of the three markers in my results showed active malignancy, at a low but still measurable level. Six months later, when we were in Boston in August, we had the test done again. On blood tested within twenty-four hours of being drawn, AMAS is 99 per cent accurate. All three markers were now negative.

I realise this may be due to a delayed effect of the chemotherapy or a build-up in hormone therapy (Megace at first, and presently – since at the moment I currently prefer spots and hot flushes to fat – Tamoxifen). But it could also be the soup. The energy – which I still find remarkable, remembering my total exhaustion after treatment – I believe is due to the supplements and reflexology as well as the remission itself.

Cancer and the mind

Since then I have become more consciously interested in the part played by the mind in cancer remission. Stephen Jay Gould, writing from experience and what he calls ‘my old-style material perspective’, is strong on the idea that attitude matters in fighting cancer, suspecting that mental states may feed back upon the immune system. The two best books I have found on cancer agree: Michael Lerner, from the perspective of a knowledgeable and experienced cancer-carer, and the Australian cancer survivor Ian Gawlor (You Can Conquer Cancer, Hill Of Content publishers, Melbourne, Australia) both place the sufferer's mental state at the heart of successful outcomes.

Above all they emphasise the importance of the patient's own involvement with their treatment, something borne out by Bernie Siegel and the Simontons’ findings, that ‘difficult’ patients do better than passive ones. By now most cancer professionals must be aware of the psychiatrist David Spiegel’s discovery (so surprising to himself) that, among his breast cancer patients at Stanford University, those who took part in group therapy lived some eighteen months longer than those who did not. Although not yet duplicated in other trials, from down here on the battlefield the results look pretty interesting. In California I went to a weekly group and found it reassuring. I liked the exchange of information, the concern that quickly grew for each member, the mutual support. Yoga, Qigong and guided relaxation all helped me during my treatment, but since then I have also spent ten days at a retreat learning Vipassana meditation, a technique that, by passing the mind continuously down and up the body while dispassionately observing all its sensations – ‘as they are, not as you would like them to be’ – can bring the practitioner into a remarkably positive and relaxed state of equanimity. Though not very experienced and a hopelessly intermittent practitioner, I have found it greatly helps my confidence: when hit by fear or despondency, I have something to fall back on.

Improving the system

What might one gather from all this, a single experience, not yet concluded? Some things are certain, others may be pointers to how better care – and, I believe, better outcomes – might be offered to the patient.

Firstly, no patient should be asked, however kindly and however overworked the hospital staff, to sit in a corridor without further inquiry, immediately after hearing they have an estimated three to four months left to live. But even after the less devastating diagnosis of primary breast cancer, most people need adjustment time before going home to do the washing up. Doctors need better training in how to break bad news. However bad the prognosis, it will still help the patient to know that the median may not be the message. And, given the real, well-validated phenomenon of spontaneous remissions in cancer, telling it as it is should never cut the patient off without leaving a chink of hope and some area of manoeuvre.

Waiting areas could finish you off

In general hospitals are not patient-friendly. Illness shrinks the patient’s confidence, and arriving for the first time at a huge NHS hospital is often a time of unnecessary anxiety. Simply finding your way around is exhausting. The NHS is obsessed with cutting waiting times – but waiting in itself is not so bad – it's the circumstances in which you have to wait that count. Overhead (sometimes even neon) lighting, interior spaces with no views out and miserable seating against the walls all contribute to extreme mental and physical enervation. Patients who arrive relatively hopeful soon start to wilt.

Waiting time could be used positively. Sitting in a pleasant, but by no means expensive room, with thoughtful lighting, a view out to trees, birds and sky, and chairs and sofas arranged in various groupings could be an opportunity for patients to relax and talk, away from home cares. An old-fashioned ladies’ room – not a partitioned toilet in a row – with its own hand basin and a proper door in a door frame - supplies privacy for crying, water for washing the face, and a mirror for getting ready to deal with the world outside again. There could be a tea and coffee machine (including herb teas) for while you're waiting, and a small cancer library, as well as BACKUP and other leaflets, for those who want to learn more about their disease. More ambitiously there could be a TV with a small library of cancer-informing tapes and, to cheer you up, a video laughter library. Norman Cousins's book, Anatomy of an Illness, makes a good case for laughter, not only as escape but as a therapy to relax the patient physically, leading to less pain and better sleep.

At the moment most hospital environments say to the patient, in effect: ‘How you feel is unimportant. You are not of value. Fit in with us, not us with you.’ With very little effort and money this could be changed to something like: ‘Welcome! And don't worry. We are here to reassure you, and your treatment will be good and helpful to you.’ Why shouldn't the patient look forward to a day at the hospital?

Information eases fear

Mentally, a simple information pack with (especially if treatment is to be in a large NHS hospital) a hospital plan, plus, say, the names of the doctors and specialist nurses, the telephone numbers and a friendly introduction to BACKUP, Macmillan Cancer Link, and other support organisations, including local self-help groups would help a lot. So would the addition of a simple sheet (with space to write the answers, and a pencil) called ‘Questions you may like to ask your doctor’ – not just for the information itself, but because the act of a nurse or carer giving me this would have indicated a support-system out there, ready to help. Feeling alone, as if set adrift in a leaky boat on a violent and hostile sea, numbs the mind and lets in despair.

But it would have been helpful practically too. Few patients hear anything much the doctor says after the word ‘cancer’. Nor do the family or friends who have come with them for support. The next doctor's appointment may be a week or more away and meanwhile ignorance breeds fear. Information is what most cancer patients cry out for – at many different levels. A guide to some questions you might want to ask your doctor could liberate those who are too timid, too conscious of taking up the doctor's time or too fearful of the answers to ask, and indicate an openness on the physician's part to let the patient participate actively in their own treatment.

Every individual makes their own map, but cancer is exhausting. Even telephoning BACKUP for the first time may be too much, both emotionally and physically. Finding a complementary therapy, even supposing you have the money to pay for it, is usually pretty random – via a friend who heard that such-and-such or so-and-so helped someone known to a friend of theirs – and an overview of what other patients have found helpful (and where it's available locally) would give patients a chance to weigh more easily the merits of these different possibilities for themselves.

It would be even better if their doctors themselves could, as the homeopathic physician George Lewith suggested in the 9 July 1994 issue of the BMJ , ‘learn the language of (complementary therapies such as) acupuncture and nutritional medicine, (so that) they have a much larger breadth of medical models through which to approach a patient’ – and through which to enter into a dialogue with the patient on how to proceed, together . We need our doctors to take an intelligent interest, and have some understanding of, the complementary therapies we may be drawn to.

Obviously a great deal more research needs to be done on nutrition and supplements in cancer care. My hunch, based not only on my, but other patients’ experience, is that actively improving diet and rectifying deficiencies that are caused in part by cancer treatments, definitely improves the patient's wellbeing. Trials on high-dose supplementation would seem to me a high priority.

Empowering the patient

Above all, what matters is not to lose the joy of living in the fear of dying. Involvement in one’s own treatment is an empowering weapon in this battle. I believe it will be proved in time to make a difference in mortality, but meantime there is a reasonable body of evidence to suggest that patients who eat healthily, keep active and take steps to deal with stress and fear, feel fewer symptoms and less pain even in the final stages of their disease. At a complementary cancer care conference at Hammersmith Hospital, a young girl spoke of how her mother had continued aerobic and dance classes to within a few weeks of her death, delighting in remaining fit and virtually pain-free – ‘She was’, said her daughter, with real happiness and pride, ‘so well when she died’.

I have no deep illusions of long survival. My chemo-remission, if I perform according to the median, is likely to end in about six months. Asthe surgeon who put in my Hickman line reminded me, early warning of further metastatic activity is not known to prolong survival. But if the next AMAS test shows positive again and the map we've made so far no longer works, there are still other things to try – and most of them work maybe 20 percent of the time. Choosing the less expensive (no point in bankrupting my family), those that least disrupt how we want to live, and as many of them as possible, I mean to keep on marching, down the tail of the statistical curve and on, into the sunset, and then, when eventually I must die, to die as well as possible.