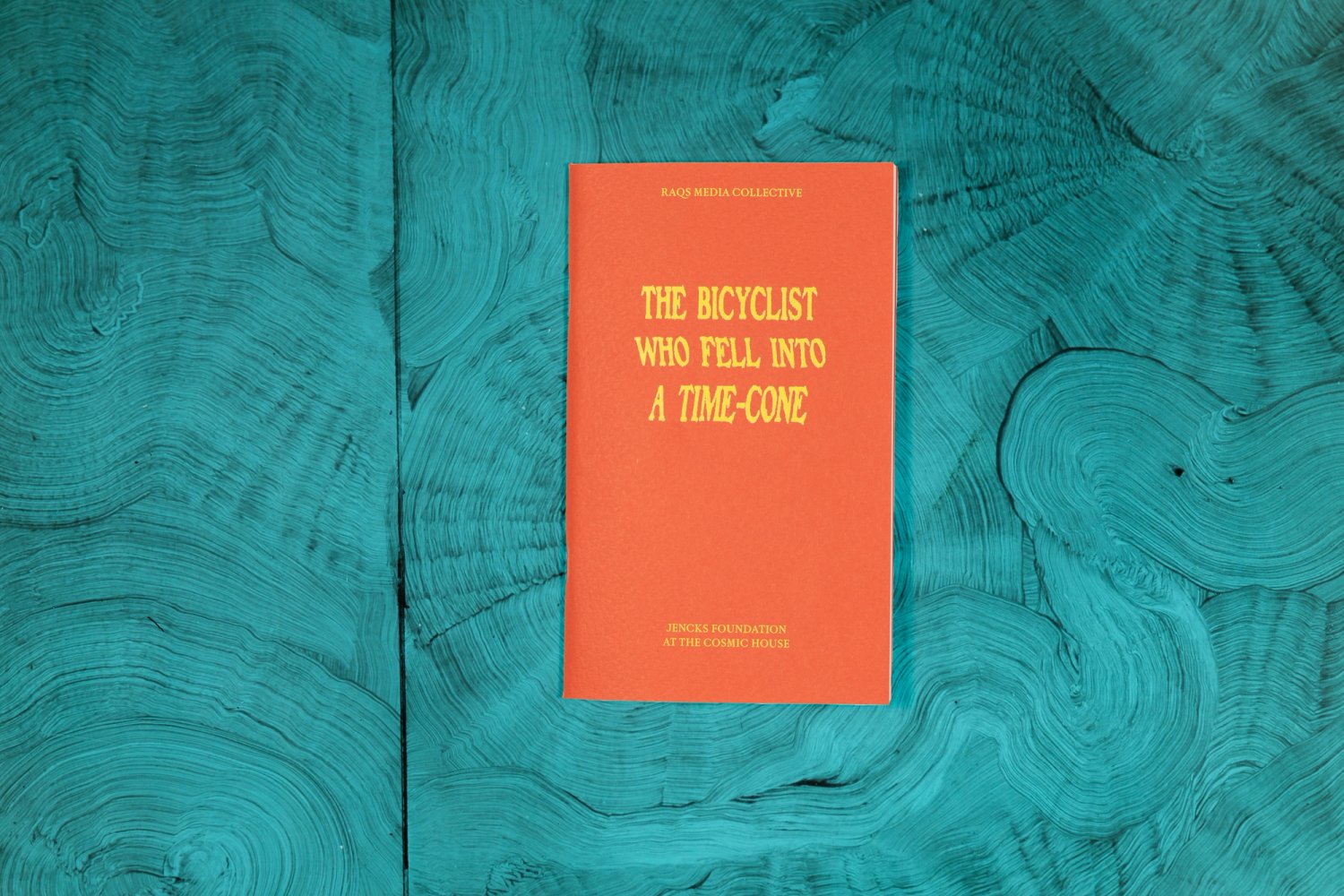

The first iteration of Raqs Media Collective’s chronogram The Bicyclist Who Fell into a Time-Cone – was conceived as a result of a specific invitation, and in response to the Jencks Foundation’s first research theme, ‘1980 in Parallax’, which took as its starting point the year 1980. This year, which marks the passage from one decade to another, is a significant moment both in the design of The Cosmic House (1978–83) and in Charles Jencks’ intellectual work, especially in relation to the first Architecture Biennale in Venice that in the same year famously announced Post-Modernism as the new international paradigm of architecture. It proposed a new canon that was to be more inclusive and polyphonic, and sought to embrace a diversity of narratives, a variety of styles and a break with linear readings of history. Yet, despite these ideals, only a few of the case studies presented at the Biennale went beyond the European and North-American context. Looking back – once again – in order to look forward, ‘1980 in Parallax’ calls to reconsider this canon from the critical distance of 43 years, and to engage voices from expanded geographical contexts. Raqs Media Collective’s site-specific exhibition at The Cosmic House (Charles’ former family home, and a built manifesto of his own version of Post-Modernism) oscillates between fact and fiction while outlining 1980 as a transient moment that left a significant mark on our collective imaginary.It borrows the term ‘parallax’ from astronomy to describe perceptions of a particular moment in history, while folding time, space, imagery and narrative to interrogate varied geographies of perceived centres and peripheries. Sharing an affinity with The Cosmic House – another complex diagram of time – Raqs Media Collective’s chronogram invites us to think about temporality and offers a method of ‘kinetic contemplation’ to destabilise mainstream narratives. It is a poetic meditation on time through time, querying the ways in which histories and memory are constructed, and in which the future is forecast. The film chronogram moves and jumps between different temporal scales and dimensions by nesting, embedding and juxtaposing contemporary footage and animation with found archival images (some sourced from Charles’ archive and his trip to Delhi in 1980). Its main protagonist, the Bicyclist, traces a circular and repetitive journey that invokes an explorative and meditative mood. This zooming in and out of time and the temporal ambiguity of the landscapes are annotated by a set of animated topological shapes and time-cones, which appear and disappear from the screen, and enter the physical space of The Cosmic House through Raqs Media Collective’s wall drawings and AR installations, entitled Betaal Tareef: In Praise of Off-time (and its Entities). The second iteration of The Bicyclist Who Fell into a Time-Cone takes the form of an artist book, and foregrounds text over image. Mirroring the film’s visual textures, the five voices in the pamphlet register varying distances from what is seen on the screen and its potential elucidations: voiceover, description of images, words on screen, added layers of annotations and meta-annotations. This cascading stream of interpretations reveals an affinity with Charles’ use of the format of the hyper-text even before the internet, an attempt to develop a more polyphonic method of writing history in dialogue, with the aim to undo dominant meta-narratives.

One of the voices from the past, Charles appears as the figure of the foreign architect who travels to Delhi in 1980. First approaching from the sky, as evident in his photographs of the Himalayas, he visits the Jantar Mantar, the eighteenth-century astronomical observatory. Charles’ 40-year-old archival slides are overlaid with contemporary images of the same site, seemingly unchanged over time. He observes a posthumous dance between the Jantar Mantar and Palika Kendra, its neighbouring twentieth-century brutalist tower – a dance that is echoed in Raqs’ chronogram as it defies linear time to enter into a new dialogue with Charles.*

Eszter Steierhoffer, Director

Jencks Foundation at The Cosmic House

* Looking at the slides taken by Jencks in his ‘archi-tistic’ study, with its slide-scrapers, we – Raqs – observe his images of his trip to New Delhi as a transport for time travel. Between an eighteenth-century astronomical observatory and its much later neighbour, the twentieth-century brutalist building built for governance, we espy US Army surplus Harley Davidson motorcycles from the Second World War left behind in Delhi. Over time these were repurposed into shared taxis, caparisoned with bright canopies and seats, with an impressive phat-phat-phat sound as they wended a rather stately way. These Phat-phatis of our pre-pubertal wanderings in the city, unbeknownst to each other, and to our own converging futures in and as Raqs, may have been an instance where the gaze of Charles Jencks may have been returned, accidentally, by a pair of our eyes, seated on a transient machine, in real time, before being dissolved into the wind that blew away that scrap of time into a little bit of void. The sky in Jencks’ photograph suggests the azure clarity of a late twentieth-century October blue in Delhi, circa 1980. Like so many things, it is our city but almost another city, another time within time, observed by us beset by other needs, unanchored, just before the disappearance of a memory, without memory.

—Raqs Media Collective

Download the full booklet, The Bicyclist Who Fell into a Time-Cone, here.